Get to Know More about Peat

Meet peat — the unsung hero hiding beneath our feet in the Interlake. It might not look like much, but this sponge-like plant material plays a huge role in keeping ecosystems healthy and our planet cool.

We’re getting down to the root of it all—what peat is, why it matters, and why protecting it is moss definitely a good idea. Lets just say, peat’s story is one worth digging into.

What is Peat?

“Peat” refers to a type of soil formed from the buildup of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter, mainly peat moss. It looks very similar to regular soil at first glance but is packed full of carbon and other nutrients. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, or fens. They forms in wetland conditions all around the world, where flooding or stagnant water obstructs the flow of oxygen, which slows the rate of decomposition.

Peat Moss:

Peat moss is made of any plant material that is prevented from decomposing due to acidic and oxygen poor conditions. It can be made of grasses, wood, or even moss. Sphagnum moss is an ecosystem engineer which creates those peat forming conditions by holding onto water and releasing hydrogen ions which cause acidification.

Peat moss, plants, and other vegetation remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in leaves, stems, branches, and roots as carbon. As the plants die and decomposition is stalled by permanently saturated conditions, this carbon slowly builds up the ground, and forms peatlands.

Peatlands:

When peat accumulates to a depth greater than 40 cm, it’s called a peatland. Peatlands in Canada are unique ecosystems usually found in the boreal ecozone. Peatlands began forming in Manitoba around 9,000 years ago, after the last ice age. Manitoba contains approximately 17% of Canada’s peatlands, representing about 90% of all wetlands in Manitoba, covering over 200,000 km2 or one third of the province.

Peatlands are defined as having at least 40 cm of peat, but most peatlands are usually a few metres deep or more. Peatlands in Manitoba generally build up new peat at a rate of around 0.5mm. This means it can take thousands of years for a single meter of peat to form!

There are two main types of peatlands in Canada — bogs and fens. Bogs are raised slightly above the surrounding landscape and have deep areas of peat. They aren’t connected to other bodies of water like lakes or rivers by ground or surface water, and they receive water only from precipitation, such as rain, snowmelt, and fog. As a result, bogs are nutrient-poor and highly acidic. Fens receive water from both precipitation and surface or groundwater sources, which introduces more minerals and nutrients to the ecosystem. Fens are found in areas with expansive flat topography where water can flower very slowly and consistently through them, along the edges of lakes and rivers and often support a diverse range of mosses, sedges, shrubs, and trees.

Ecosystem Health

Peatlands are one of nature’s most powerful climate allies. They store lots of carbon, more than all the world’s forests combined—locking it safely in the ground for thousands of years. When left undisturbed, peatlands act as a carbon trap, helping to keep our planet’s climate stable. Disturbing or draining them releases this stored carbon into the air, speeding up the process of climate change. Protecting peat where it is means protecting one of our most effective natural defenses against global warming.

Culture and Medicine

Peatlands play important roles related to health and culture, nurturing many of the 546 plants that Indigenous peoples use for medicine. Some of the medicinal plants traditionally harvested from peatlands include:

- Berries – Indigenous groups throughout northern North America have harvested various berries from bogs, including bog cranberries, bog blueberries and bakeapple (aka – cloudberry, salmonberry).

- Sphagnum moss – Used as a diaper material, as a menstrual product and for bandages.

- Common sundew – used to remove warts, corns, and bunions.

Some of the cultural plants traditionally harvested from peatlands include:

- Cotton grass – used for making kudlik (soapstone lamp) wicks and bandages.

- Sedges – are used for making floor coverings and woven mats.

- Sphagnum moss – the Inuit, built semi-subterranean houses using blocks of peat.

“If archaeologists and ethnobotanists were to devote more effort to understanding the use and significance of peat bogs by Indigenous groups, it is likely that perception of bogs would eventually shift from marginal places to valuable and important components of cultural landscapes.”

-(Speller, J. and Forbes, V., 2022)

What is Peat Harvesting?

Did you know the potting soil purchased from garden centres is most often peat moss?

Canada is the largest producer of peat in the world, harvesting around 1.3 million tonnes of peat in 2010 (that’s equal to 1.3 million hippos!). There are two types of peat harvested in Manitoba, sedge and sphagnum peat moss.

How is it harvested?

First, the surface water is drained and cleared of all surface vegetation. Then it is raked to dry out the top few layers. Once dried, the peat is harvested with an industrial vacuum. Once harvested, the peat is transported to a processing facility.

What happens after peat is harvested?

If restoration is pursued on a harvested site, the goal is generally to return it to a ‘peat accumulating ecosystem.’ Water levels are raised to re-establish an anaerobic environment conducive to peat accumulation. The Moss Layer Transfer Technique involves transferring mosses from healthy donor sites to degraded areas. The transferred mosses help kickstart the growth of peat-forming plant communities, supporting the restored peatland in returning to ‘a state of peat accumulation’. However, the carbon released during harvesting and the sequestration loss by degrading these ecosystems remains a concern.

Can it return to its natural state?

The Peatlands Stewardship Act requires peat harvest licence holders to develop sustainable Peatland Management and Recovery Plans, aimed at ensuring long-term stewardship of these vital landscapes. The Act strengthened the rules and regulations regarding peatland harvest and restoration. If a peatland is harvested, it must be restored to a wetland. While the restored wetland will have lost the carbon stores depleted through harvesting and may have reduced ability to sequester carbon if not restored to a peat-accumulating wetland, a restored wetland is expected to support other ecological values such as supporting flood and drought resiliency, providing habitat, and recreation opportunities.

What are the Effects of Peat Harvesting?

Air:

When peatlands are drained and the surface layer of the bog or fen is exposed to oxygen, it begins to decompose rapidly, releasing stored carbon into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas, which means it contributes to climate change through the greenhouse effect. Disturbing these large carbon sinks not only causes immediate emissions but also stops the impacted area from sequestering new carbon until restoration work is done.

Water:

Peat harvesting can also have an effect on local water quality, as some peatlands prevent heavy metals from flowing out of the wetland. Lake Winnipeg, the 10th largest freshwater lake in the world, has been under severe ecological stress due to nutrient overloading (aka too much phosphorus and other nutrients). This overloading has resulted in algae blooms and beach closures affecting recreation and the fishing industry in the lake.

Learn more about the effects on water here.

Species:

The layers of peat and live mosses form a surface in which other plants grow. Because of the low levels of nutrients and oxygen, especially in bogs, plant diversity is often restricted to specialized species such as labrador tea, cranberry, bog laurel, pitcher plants, orchids and fungi. Other species that are unique to these regions include – millions of songbirds, migratory birds and waterfowl, moose, caribou, black bears, wolves, small bugs and insects.

These species often rely heavily on peatlands as breeding grounds and stopover habitats on long migration routes. Because of the reliance on these unique ecosystems, impacts to peatlands may affect the species that inhabit them.

What is a Provincially Significant Peatland?

Some peatlands are recognized by the Province as Provincially Significant Peatland because they’re so important for nature. In these areas the following activities are not allowed:

- logging or any other type of forestry activity or any type of agricultural activity.

- harvesting peat

- mining, the development of oil, petroleum, natural gas or hydro-electric power

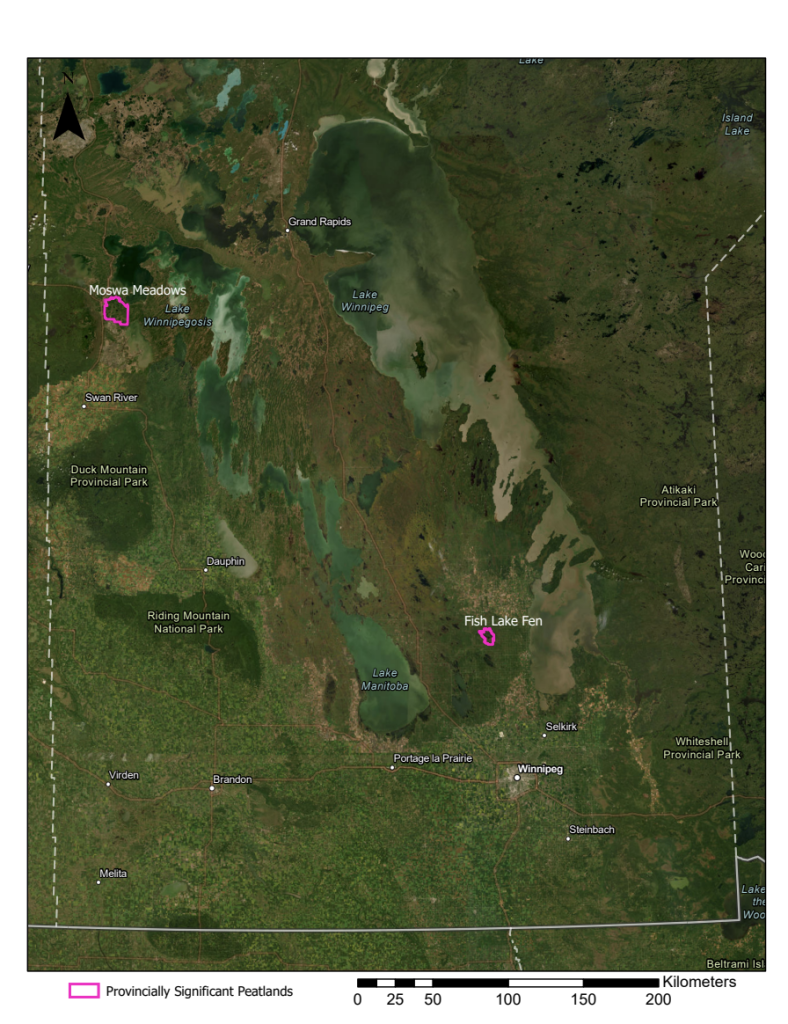

Building on this Manitoba-made legislation, two Provincially Significant Peatlands were officially designated in January 2023: Fish Lake Fen in the southern Interlake region and Moswa Meadows in northwestern Manitoba. Together, these peatlands protect nearly 28,000 hectares of land (that’s the size of Kitchener, Ontario).

Importantly, these protected peatlands remain open to the public for personal recreational and traditional uses. For example, activities such as hunting, fishing, foraging, medicine gathering, birdwatching, and hiking are all allowed.

Why Peatlands Matter

While peatlands might not draw much attention at first glance, but they are quietly doing some of the planet’s heaviest lifting. These ecosystems store massive amounts of carbon, help filter water, and provide essential habitat for countless species.

However, the future isn’t guaranteed. As peat harvesting continues and climate pressures grow, protecting these ecosystems becomes more important than ever. Manitoba has made important strides with legislation and new protected areas. For example, Fish Lake Fen and Moswa Meadows, but there’s still work to do.

By valuing peatlands for more than just what can be extracted from them, we can ensure these natural carbon rich ecosystems remain intact for future generations. Whether you’re hiking, birdwatching, or simply learning more, every step toward awareness and stewardship helps keep peatlands thriving.

Learn More:

Read more on our Blog – FRCN Acquires Peat Harvesting License from Sungro Horticulture

Learn more in the Wildlife Conservation Society Canada article on Northern Peatlands

Read more in the IISD report for Peatland Mining in Interlake Manitoba

Learn more in the Manitoba government’s peatlands management plan.

Read more in The Narwhals article “Manitobans rally to oppose proposed new peat mining project.”